Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Technically this is my 101st weekly column in this space, given that the last couple of weeks were devoted to a two-parter covering two of my very favorite subjects, boundless sorrow and self-slaughter. But this is my place, and I make the rules, so welcome to the Bombast centenary celebration.

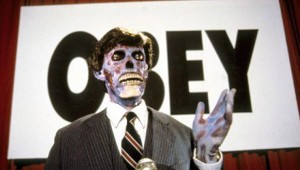

In its nigh on two years of life, the venerable American institution that is Bombast has endured a humiliating masthead change, while watching its author’s career arc closely follow that of Stanton “Stan” Carlisle in Nightmare Alley. It has reported on the bleak clowning of a senescent Jerry Lewis and smoked out the reclusive Terrence Malick. It has bravely faced down such menaces as erroneous aesthetic and moral judgment, the sausage fest of cinephilia, comments section goons, reverse snobbism, Vulgar Auteurism (sp?), and the quite dead Vincent Canby. It has sung hosannas to the brief heyday of the MoMA Gramercy theatre, the Reverse Shot webzine, George Wesley Bellows, and Emile Meyer. It has exhumed Saints of the cinema, faced the pandemonium of the present, and tried manfully to get a grip on the future. Yes, throughout all of this, the gold and platinum No Limit Records tank that is this column has kept rolling on, impervious!

As I began writing this latest installment, the steady cascade of #Sharknado Tweets had been underway for an hour, all of America online collectively giving the Mystery Science Theater 3000 treatment to the Syfy channel’s airing of the latest product from ‘mockbuster’ studio The Asylum. This surely counts as one of the week’s big events, along with the ribbon-cutting on Pitchforkmedia’s new movie chat site, The Dissolve. (I have not had time to give The Dissolve a more than cursory glance, but I will say their thumbnail portrait artist has failed to do justice to Sam Adams. On that basis, I give the whole production a 5.2.) The official trailer for Paul Schrader’s much-anticipated The Canyons has also surfaced, beginning with star Lindsay Lohan delivering a eulogy for the end of “seeing a movie in the theater.” Perhaps, then, it’s best not to kick off the No. 100 festivities by celebrating The State of Cinema which, all things considered, usually makes me feel like the conclusion of Tsai Ming-Liang’s Vive L’Amour.

Image may be NSFW.

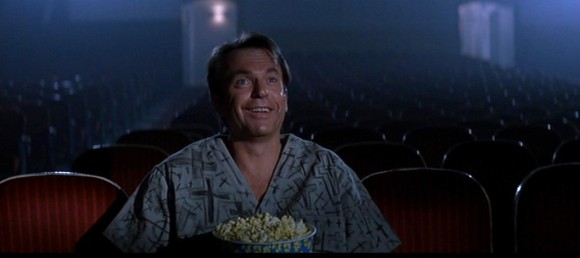

Clik here to view. The more obvious Tsai citation would be Goodbye, Dragon Inn, which I wrote about for the Winter 2004 edition of Reverse Shot. The film is set in Taipei’s Fu-Ho Grand movie theater on the eve of its closure, and is full of the same imagery of the dilapidated-cinema-as-abandoned-husk that opens The Canyons’ trailer. King Hu’s 1966 Dragon Inn is screening at the Fu-Ho on its last night, a film seen playing to a capacity first-run crowd in the prologue: “Tsai begins with a séance,” reads my slightly purplish write-up, “evoking a lost, perhaps never-existent paradise where undiluted cinematic grace gave form to a [sic] unpretentious collective dream, an era of egalitarian pop poetry eulogized by the bygone celluloid swordsmen who wearily conclude in the post-screening lobby ‘No one comes to the movies anymore.’”

The more obvious Tsai citation would be Goodbye, Dragon Inn, which I wrote about for the Winter 2004 edition of Reverse Shot. The film is set in Taipei’s Fu-Ho Grand movie theater on the eve of its closure, and is full of the same imagery of the dilapidated-cinema-as-abandoned-husk that opens The Canyons’ trailer. King Hu’s 1966 Dragon Inn is screening at the Fu-Ho on its last night, a film seen playing to a capacity first-run crowd in the prologue: “Tsai begins with a séance,” reads my slightly purplish write-up, “evoking a lost, perhaps never-existent paradise where undiluted cinematic grace gave form to a [sic] unpretentious collective dream, an era of egalitarian pop poetry eulogized by the bygone celluloid swordsmen who wearily conclude in the post-screening lobby ‘No one comes to the movies anymore.’”

The above was written when I was, I suppose, 23 years old. This was so long ago that the Web 1.0 page on which these words appear was rendered in white font on a black background, a layout that designers have subsequently learned actually makes readers’ eyeballs explode. What I did manage to read of this juvenilia, through an improvised pinhole viewer of the sort that one uses to gaze on a solar eclipse, was entirely heartfelt and at least mostly legible, if not up to the measure of Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. And what’s interesting and amusing to reflect on is that, during the entire time that I have been writing about movies, the movies have been considered a terminal case.

Which, of course, they always have been—a premise that my colleague Leah Churner and I had a little bit of fun with last year. There’s no denying, though, that unprecedented changes have been afoot in the 101 weeks of this column’s existence. Here is Schrader, from an interview conducted earlier this year: “For the most part theatrical no longer does straight drama. The idea of the conventional drama has migrated to television or cable… You lose the theatrical experience, that’s a genuine loss, but on the other hand you now have an art house cinema in every living room. Is it better or worse? Doesn’t matter. It’s different. Make the most of it.”

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Certainly Sharknado director Anthony C. Ferrante, interviewed during his moment of, er, triumph, sees a new world of boundless prospects: “All these fans just embraced this crazy little movie we did and turned it into this thing which, I mean, I’m just, like thrilled. I’ve been making movies for a very long time and I’ve never had this many eyeballs on anything I’ve ever done, and having this communal experience live-tweeting. You’re not seeing it in a movie theater, but it’s even better, because I’m getting to play with people on Twitter and talk about it.” The preceding was posted on Internet-chumming clickbait-generator Buzzfeed, who by 11:03 PM last night–the movie aired at 8:00–had posted a feature called “The 7 Best/Worst Lines of Sharknado,” which was probably viewed by more people than there are extant copies of Negative Space.

Certainly Sharknado director Anthony C. Ferrante, interviewed during his moment of, er, triumph, sees a new world of boundless prospects: “All these fans just embraced this crazy little movie we did and turned it into this thing which, I mean, I’m just, like thrilled. I’ve been making movies for a very long time and I’ve never had this many eyeballs on anything I’ve ever done, and having this communal experience live-tweeting. You’re not seeing it in a movie theater, but it’s even better, because I’m getting to play with people on Twitter and talk about it.” The preceding was posted on Internet-chumming clickbait-generator Buzzfeed, who by 11:03 PM last night–the movie aired at 8:00–had posted a feature called “The 7 Best/Worst Lines of Sharknado,” which was probably viewed by more people than there are extant copies of Negative Space.

This week I’ve been re-reading my copy of the Kevin Jackson-edited Schrader on Schrader & Other Writings—which, as evinced by the jacked spine of my copy, is one of the oldest film books that I own, if not the oldest. In particular, I have been re-reading the selections of Schrader’s criticism taken from his stint at the Free Press, work published in LA-based glossy vanity magazine Cinema during his editorial stewardship, and Film Comment. These pieces were produced when Schrader was about the same age that I was when writing about Goodbye, Dragon Inn, and the comparison is, frankly, the sort of thing that makes one want to heave one’s laptop down the nearest available well in despair.

As a critic, Schrader owed an admitted debt to Parker Tyler, author of 1947’s Magic and Myth of the Movies, a largely forgotten figure today but influential in shaping the idea of cinema a kind of ceremony for the ambitious young writer from Dutch Calvinist Grand Rapids. Schrader had ditched Calvin for Jung in college and, in the act of transposing his religious faith to cinema, was attracted to Tyler’s writing for obvious reasons, for it spoke of the movies’ language of larger-than-life archetypes, of “the ritual importance of the screen, its baroque energy and protean symbolism.”

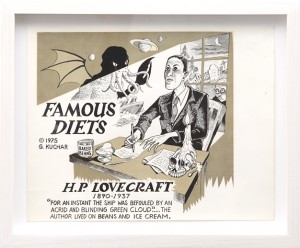

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Schrader lost the faith of his youth, but not its forms. When he films sex, he makes an altar of the bed. When he references John Ford’s The Searchers or the conclusion of Bresson’s Pickpocket, as he does in his work time and again, it’s less an homage than an invocation, the repetition of a creed. His 1982 Cat People begins with a prehistoric human sacrifice. His 1987 Light of Day deals, if sometimes unconvincingly, with rock n’ roll as a transformative rite. 1992’s The Comfort of Strangers, a film bookended by Christopher Walken’s rehearsed, incantation-like monologues, is concerned with a complex esoteric blood ritual enacted by Walken and Helen Mirren amid the Renaissance bric-a-brac of their Venetian flat. And 1985’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters may be Schrader’s most complex work about life wholly submitted to ritual, ending in its subject’s performance-piece attempt at a military putsch and seppuku suicide.

Schrader lost the faith of his youth, but not its forms. When he films sex, he makes an altar of the bed. When he references John Ford’s The Searchers or the conclusion of Bresson’s Pickpocket, as he does in his work time and again, it’s less an homage than an invocation, the repetition of a creed. His 1982 Cat People begins with a prehistoric human sacrifice. His 1987 Light of Day deals, if sometimes unconvincingly, with rock n’ roll as a transformative rite. 1992’s The Comfort of Strangers, a film bookended by Christopher Walken’s rehearsed, incantation-like monologues, is concerned with a complex esoteric blood ritual enacted by Walken and Helen Mirren amid the Renaissance bric-a-brac of their Venetian flat. And 1985’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters may be Schrader’s most complex work about life wholly submitted to ritual, ending in its subject’s performance-piece attempt at a military putsch and seppuku suicide.

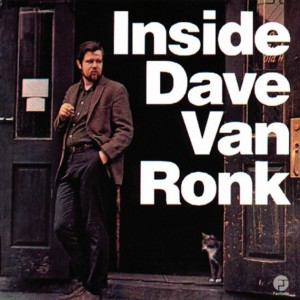

The Platonic screening ideal, the ritual through which Tyler, Schrader, and Tsai were inducted into the Church of Cinema, is gradually going the way of Latin Mass. The old secular cathedrals of cinema, the still-standing movie palaces in urban centers, have long ago been sanctified, converted to churches. Cinephiles that fetishize 35mm are a revanchist sect, as quaintly antique as French Legitimists, though without comparable social standing. I thought of this while doing my other bit of reading for this week, the posthumously published memoir of a True Believer in the literal Magick of the medium, Curtis Harrington. Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood: The Adventures of an Aesthete in the Movie Business was released in June by Drag City Books in Chicago; reviewing the book, I quoted one passage in fragment that I would like to quote here in full:

“I was always aware of the great difference that there is between film and television. It is more than just the obvious physical difference. It is also profoundly metaphysical. For instance, even for those with a smattering of astrological knowledge, it can be understood that cinema is under the planet of illusion, Neptune, whereas television falls under the influence of the planet Uranus. A film offers refracted light from a screen; television images are self-contained electronic impulses… As I write, the word is out that in the next few years film will disappear, and only digital reproduction will remain. This sad state of affairs is, for me, almost too terrible to contemplate, and yet I must remind myself that film came out of a technological revolution, and therefore it must be inevitable that another technological revolution will replace it. This is at once the curse of film and perhaps its long-term salvation. It becomes more permanent as it becomes more evanescent. Just as the development of sound-on-film technology doomed the silent film as a creative medium, now digitization will doom film itself. It is as if the painter’s traditional pigments have been replaced by artificial colors that could never match the qualities that made older paintings great. Films can be reproduced on television, or made with digital technology, but a real film is in the magic of refracted light on a screen, of moving shadows.”

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Stoic, sagacious words from a man nearing 80. Harrington’s creative career had for most purposes ended twenty years before he wrote them—but how are we the living to carry on in this Age of Uranus? Better to pack it in? I seem to recall Kenneth Tynan recommending that no critic should hang on to the job for more than five years—or was it ten? (As luck would have it, I have never had a job per se, so whew!) Here is Renata Adler, who tenuously held the post of New York Times film critic from 1968-69, in an interview with The Guardian this week: “Everybody has opinions about films anyway, so who wants to hear the shrew that is oneself? To do this for years and years?”

Stoic, sagacious words from a man nearing 80. Harrington’s creative career had for most purposes ended twenty years before he wrote them—but how are we the living to carry on in this Age of Uranus? Better to pack it in? I seem to recall Kenneth Tynan recommending that no critic should hang on to the job for more than five years—or was it ten? (As luck would have it, I have never had a job per se, so whew!) Here is Renata Adler, who tenuously held the post of New York Times film critic from 1968-69, in an interview with The Guardian this week: “Everybody has opinions about films anyway, so who wants to hear the shrew that is oneself? To do this for years and years?”

While the 21st century has thus far displayed a dispiriting tendency to promise the world and deliver only Sharknados, the very fact of the seismic changes underway in cinema—better today to say “moving pictures”—makes me think there may still be story worth covering here. That story will probably have very little to do with what’s happening at the multiplex, as budget is all that remains to distinguish blockbuster from mockbuster. (I write this having not yet seen the touted Pacific Rim, but having yesterday watched White House Down with a weekday matinee crowd of a half-dozen obvious depressives.) It will more likely be concerned with moving pictures that are like “the small, portable, intelligent unit fighting the dinosaur” described by Robert Fripp in a 1978 interview. Or with—what?

“May you live in interesting times” goes the so-called “Chinese curse” that was never attributed to a Chinaman, proof enough that specious pseudo-knowledge did not begin with the Internet. Onward then to the prospect of new enthusiasms, new technologies, new rituals, and, when those inevitably disappoint, new pieces of the past to excavate! Goodbye to The Crowd! Hello to the new fragmented unity!

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound magazine and sundry other publications. He lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow Nick on Twitter @NickPinkerton.